Innovation as chemistry

Cumulative culture and exponential technological change

Welcome to the fifth issue of the Evolving Impact newsletter, exploring technology, culture and complexity in the context of global development and humanitarian aid.

Dear reader,

Despite cash transfer programming (CTP) being widely hailed as an innovation in humanitarian aid, Karen Peachey, former director of the Cash Learning Partnership (CaLP), has questioned whether it is truly a novel idea. In 2019 I co-organised a conference on humanitarian innovation in The Hague and Karen gave the keynote. In a subsequent write-up, she says:1

“The use of cash in humanitarian response is not innovative per se. Cash has been used in relief operations since the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–71, and we even find reference to cash as part of a flood response in the Old Testament of the Bible.”

In the past 20 years we have simply re-discovered the practical and moral case for using cash in humanitarian response rather than distributing in-kind assistance. This re-discovery has been accompanied by technological developments that are helping to facilitate the secure transfer of money to large numbers of people.

While mobile phones were first used to provide financial services in the early 2000s, there have been big advances in recent years. Between 2017 and 2022 there was an almost 10-fold increase in mobile money accounts worldwide, from 174 million to 1.6 billion.2 This growth is reflected in increased use of digital payments for CTP.3

Other technological advances are also having an impact on CTP (as well as creating new risks). Biometric technologies are being used to reduce fraud, duplication, and meet donor assurance requirements.4 Blockchain-based ID management systems are helping to put aid recipients in control of their data.5 Artificial intelligence will no doubt create further opportunities and risks.

Thus, the cash agenda has come to the forefront of humanitarian aid at a particular time when the combination of old ideas and new technologies has presented an opportunity for radical change. This story is not unique. Under careful examination, every innovation is built from the foundations of existing knowledge — by combining ideas from different domains and joining the dots in new ways.

Throughout most of history it was thought that only humans exhibited culture, understood as ”information acquired from other individuals via social transmission mechanisms such as imitation, teaching, or language.”6 But in recent decades, research has shown that social learning is widespread in nonhuman species.7

Several nonhuman species also display group-specific cultural traditions. In Guinea and the Ivory Coast chimpanzees have been observed cracking open nuts by placing them on a large flat stone and hitting them with a smaller stone. But in Tanzania there are groups of chimpanzees that have never been observed using this method, even though both nuts and suitable stones are present.8

Today, theorists posit that what truly makes humans unique is cumulative culture, arising from our unique metacognitive abilities.9 Only humans demonstrate the ability to accumulate cultural knowledge over time, gradually improving existing practices, technologies, and institutions, and combining these cultural artefacts in new ways to make further advancements.

At the beginning of humanity’s technological journey we learned how to make bladed tools using methods not dissimilar to those displayed by the chimpanzees in Guinea and the Ivory Coast. But we also learned how to make fire, and then to use fire to extract metals from ores and make better tools. An early cluster of technologies and corresponding craft of practice began to form.10

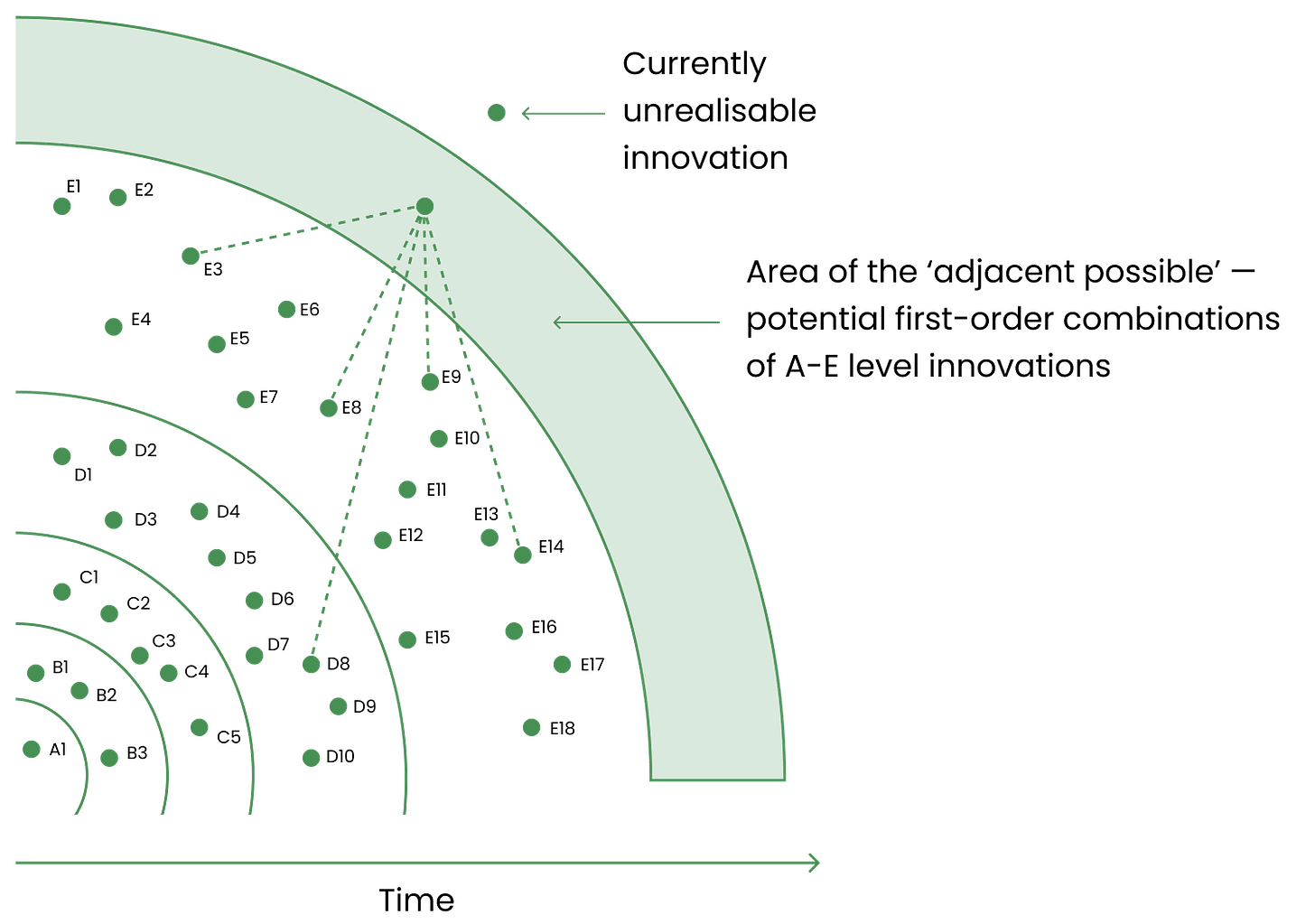

The cumulative nature of technological development means that as new technologies are developed, the number of possible combinations also increases, creating a positive feedback loop that fuels continued development. As the field of technologies grows, new ‘adjacent possible’ combinations are revealed.11 Hand axes were made possible by preceding developments in woodwork (to make the handle), metalwork (to make the blade), and braiding fibres (to bind the blade to the handle).

If you sense that the world is speeding up, there is plenty of evidence to suggest you are right. Increased connectivity has arguably been the great driver of scientific and technological innovation throughout history.12 As knowledge and technologies have accumulated and more possibilities have opened up, the growth of the internet has massively increased our ability to connect people and ideas, further stimulating innovation.

Technology analyst Azeem Azhar argues that the acceleration is specifically connected to rapid developments in four families of technologies which are unlikely to slow down. Alongside computing and the internet, Azhar identifies biology, energy, and manufacturing as domains of technology that are each growing at an exponential rate while increasingly intersecting in different ways, creating vast potential for further combination.13

According to W.B. Arthur we are transitioning from the “economy as machine” to the “economy as chemistry.”14 The possibilities for innovation are increasing rapidly as we move from seeing technologies primarily as independent artefacts with a fixed purpose to seeing them as "an open language" made up of "objects that can be formed into endless new combinations."15

We have already seen how the ongoing evolution of cash transfer programming is happening in concert with developments in computing and biometrics. In many ways the shift from a relatively mechanistic model of in-kind assistance to a model of aid delivery that is highly networked and dependent on an array of technologies exemplifies this broader shift that is occurring in the nature of technological change.

Elsewhere, in manufacturing Field Ready have pioneered the of use of cutting edge techniques such as 3D printing to make humanitarian supplies in the field, including replacement parts for water systems in South Sudan and medical devices in Syria. In Kenya, UK FCDO partnered with Kijenzi during the COVID-19 pandemic with a similar focus on using 3D printing to manufacture healthcare products.

As energy moves from a commodity, controlled by a handful of powerful exporters, to a modular technology, huge gains are being made. In the first half of 2024 alone Pakistan acquired a “staggering” 13GW of solar capacity — approximately 28% of its entire electrical generation capacity in 2023.16 In the humanitarian space, Kube Energy have led work to install solar capacity at a big humanitarian base in South Sudan, with hopes to reduce energy costs by 50% over 10 years.17

Since 2016 UK FCDO’s Frontier Tech Hub has supported 75 projects with an explicit focus on applying cutting-edge technologies to development and humanitarian problems. The Hub’s focus includes web3, drones, blockchain, sensors, 3D printing, Internet of Things, machine learning, and geospatial data18 — a cross-section of technologies that broadly corresponds with the four domains of exponential change identified by Azhar.

If current trends continue, the exponential growth of technologies in the fields of computing, biology, energy, and manufacturing will reverberate around the world, greatly influencing global development and humanitarian aid efforts. In this age of accelerating change, the challenge lies not only in keeping pace and harnessing these technologies but in ensuring they are deployed ethically, equitably, and inclusively.

The combinatorial nature of innovation makes it a necessity to forge new connections and collaborate with a diversity of actors, bringing together different sets of knowledge and experience. By recognising that each breakthrough is built on the cumulative progress of previous generations of ideas, we are reminded that the possibilities of tomorrow depend on the choices that shape technologies today.

Thanks for reading.

What else?

🚛 A systematic review of innovation in humanitarian logistics has identified numerous gaps including involvement of beneficiaries, focus on reconstruction, and using supply chains to position organisations in ways that meet donor demands. Anyone got any funding for a challenge?

🧠 A new paper from Start Network presents an overview of local, indigenous, and traditional knowledge within the network, recommending further integration into work on early and anticipatory action in particular.

🌱 A great article in The Continent on the extensive influence of the Gates Foundation over agriculture in Africa and its role in the collapse of Zambia’s food system. Accusations of ‘playing god’ and getting it wrong. I’ll be revisiting this one in the coming weeks.

🏆 The OECD has published a new report documenting lessons from efforts to foster innovation in low- and middle-income countries through challenge funds and prizes suggesting their best use as a strategic part of a portfolio of interventions.

And finally: This newsletter is pretty niche. If you know anyone else interested in digging beneath the jargon and buzzwords to explore the nature of innovation and what it means for development and humanitarian impact, please share it with them.

I write as way to reflect, learn, and make sense of things, so everything is typed by hand without any inputs from AI. I sometimes use ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Aria for brainstorming, research, and relating ideas, but all sources are cross-checked, reviewed, and referenced.

Peachey, K. (2019) ‘How the Cash Learning Partnership supports the scaling of cash’, Elrha, 15 August. Available at: https://medium.com/elrha/how-the-cash-learning-partnership-supports-the-scaling-of-cash-aee3bbbdc26c

Figure for 2017 from: McCormack, R. et al. (2018) The State of the World’s Cash 2018. Cash Learning Partnership (CALP). Available at: https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/state-of-the-worlds-cash-report/. Figure for 2018 from: Hart, K. et al. (2023) The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Cash Learning Partnership (CALP). Available at: https://www.calpnetwork.org/collection/the-state-of-the-worlds-cash-2023-report

Hart, K. et al. (2023) The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Cash Learning Partnership (CALP). Available at: https://www.calpnetwork.org/collection/the-state-of-the-worlds-cash-2023-report

Hart, K. et al. (2023) The State of the World’s Cash 2023. Cash Learning Partnership (CALP). Available at: https://www.calpnetwork.org/collection/the-state-of-the-worlds-cash-2023-report

Jodar, J. et al. (2020) The State of the World’s Cash 2020. Cash Learning Partnership (CALP). Available at: https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/the-state-of-the-worlds-cash-2020-full-report

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html

Dunstone, J. and Caldwell, C.A. (2018) ‘Cumulative culture and explicit metacognition: a review of theories, evidence and key predictions’, Palgrave Communications, 4(1), pp. 1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0200-y

Arthur, W.B. (2011) The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves. New York: Free Press. Available at: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Nature-of-Technology/W-Brian-Arthur/9781416544067

Planing, P. (2017) ‘On the origin of innovations—the opportunity vacuum as a conceptual model for the explanation of innovation’, Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 6(1), p. 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-017-0063-2

Johnson, S. (2010) ‘Where Good Ideas Come From’, 17 September. Watch:

Azhar, A. (2021) Exponential: How Accelerating Technology is Transforming Business, Politics and Society. London: Penguin Books. Available at: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/441674/exponential-by-azeem-azhar/9781847942920

Arthur, W.B. (2011) The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves. New York: Free Press. Available at: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Nature-of-Technology/W-Brian-Arthur/9781416544067

Arthur, W.B. (2011) The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves. New York: Free Press. Available at: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Nature-of-Technology/W-Brian-Arthur/9781416544067

Azhar, A. (2024) ‘🌅 The rooftop energy revolution no one knew about’, Exponential View, 14 August. Available at: https://www.exponentialview.co/p/the-rooftop-revolution

Kube Energy (2018) ‘Solarising humanitarian operations - Elrha’, Elrha, 8 August. Available at: https://www.elrha.org/project-blog/solarising-humanitarian-operations

Frontier Tech Hub (n.d.) ‘Technologies’. Available at: https://www.frontiertechhub.org/learn/technologies