The promise of cultural evolution

Can evolution provide a high-level theory for humanitarian innovation?

Welcome to the sixth issue of the Evolving Impact newsletter, exploring technology, culture and complexity in the context of global development and humanitarian aid.

Dear reader,

“Once upon a time there was a sweet little girl. Everyone who saw her liked her, but most of all her grandmother….”

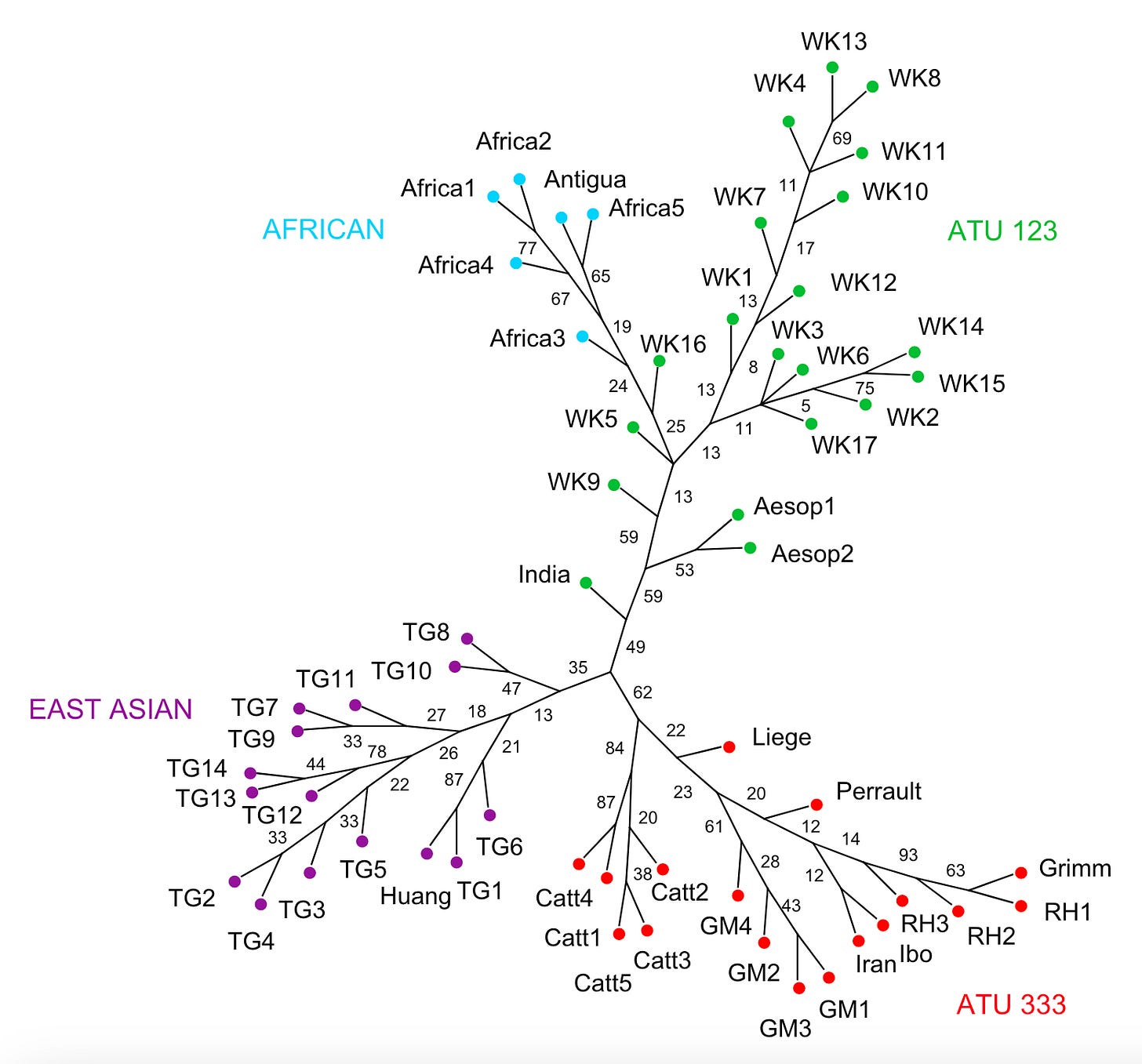

It should not be a spoiler to tell you that this story does not end well for the little girl. A wolf proceeds to eat her grandmother, put on her grandmother’s clothes, and then trick the little girl and eat her as well. If you’re from Europe you probably know this cautionary folktale as ‘Little Red Riding Hood,’ but similar stories have been identified around the world, including ‘The Wolf and the Kids’, told throughout Europe and the Middle East, and ‘Tiger Grandmother’ told throughout in East Asia.1 Folklorists have long believed that similarities between folktales across different cultures are more than coincidence, and have sought to trace their intertwined histories.

Most modern versions of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, including the version told by the Brothers Grimm, are thought to originate from a story published by Charles Perrault in France in the 17th century. This, in turn, is thought to be based on a tale called ‘The Story of Grandmother.’ Another variant shows up in a poem by an 11th century priest in Liege. Meanwhile, ‘The Wolf and the Kids’ has been traced back to an Aesopic fable first recorded around 400AD. Due to its similarities with both ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ and ‘The Wolf and the Kids’, it has been postulated that ‘Tiger Grandmother’ preceded both, but it wasn’t recorded until the 18th century.2

A study by Jamshid Tehrani at Durham University sought untangle this complex history, made even more challenging as such tales are often passed on through oral traditions. Tehrani was able to provide convincing evidence that ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ and ‘The Wolf and the Kids’ in fact have separate origins, and the tale of ‘Tiger Grandmother’ arose later as a blend of both, rather than preceding them. Several African folktales also have their origins in the story of ‘The Wolf and the Kids,’ which is further related to an Indian variant known as ‘The Sparrow and the Crow.’3

What is particularly noteworthy about Tehrani’s study is that its conclusions were reached using phylogenetic research methods more commonly used to study how organisms are related through biological evolution. Moreover, phylogentic analysis and other related research methods have been used to study the development and spread of many cultural traits in recent years, including other nonmaterial traits such as religious beliefs and puberty rites, and material artefacts such as Palaeoindian projectile points and Turkmen rugs.4

It was Charles Darwin himself who first drew a parallel between biological evolution and the evolution of culture, writing in The Descent of Man: “The formation of different languages and of distinct species, and the proofs that both have been developed through a gradual process, are curiously parallel.”5 However, early application of Darwin’s ideas to describe cultural change were highly flawed, confusing evolution with unilinear progress and reinforcing racist and colonialist ideologies in the process. By the early 1900s the field was discredited and the biological and social sciences separated.6

It is only since the 1980s that interest in evolutionary theories of culture has revived. The publication of Cultural Transmission and Evolution by Luigi Cavalli-Sforza and Marcus Feldman (1981) and Culture and the Evolutionary Process by Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson (1985) reignited the field by developing quantitative models that properly described a theory of cultural change, including the mechanisms by which cultural traits are transmitted across a population and vary over time.7 Over the last two decades there has been an explosion of research on cultural evolution generating a wealth of empirical evidence.8

At its core cultural evolution theory (CET) proposes that cultural traits are subject to the Darwinian forces of variation, selection, and inheritance.9 CET is therefore grounded in the broader theory of universal Darwinism which posits that Darwin's theory of evolution can be extended beyond the field of biological evolution to explain growth and change in a range of different domains, including the propagation of human culture and innovation in market economies.10

While the term ‘universal Darwinism’ was coined by the biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, many of the ideas behind the theory were developed by the philosopher Daniel C. Dennett. In his 1995 book, Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Dennett explains how Darwin's Origin of Species makes both an empirical argument for natural selection and a logical argument for how the underlying process would produce a certain set of outcomes. Dennett describes this latter argument as a substrate-neutral “evolutionary algorithm.”11

The assertion that evolution is an algorithmic process that can be untethered from biology is referred to as “Darwin's dangerous idea” due to its profound implications in many areas of life. Like the Xenomorph blood of philosophical theories, Dennett describes evolution as a “universal acid [that] eats through just about every traditional concept, and leaves in its wake a revolutionized world-view, with most of the old landmarks still recognizable, but transformed in fundamental ways.”12

Within the theory of cultural evolution, the evolutionary forces of variation, selection, and inheritance are accompanied by processes of cultural migration and cultural drift, and deepened by an understanding of selection across different levels, including individual selection and cultural group selection.13 Notably, it is not argued that biological evolution and cultural evolution work in precisely the same way. Cultural evolution adheres to Darwin’s theory of evolution, but not necessarily to the details of genetic evolution discovered by biologists subsequent to Darwin. While there are parallels, many specific operators differ.14

Richard Dawkins famously coined the term ‘meme’ to describe a theoretical cultural replicator — the basic unit of selection equivalent to the gene in biological evolution. But the field of ‘memetics’ lost ground after failing to demonstrate that such a discrete unit of culture exists.15 More recent theories of cultural evolution have shown that high-fidelity inheritance, necessary for selection and amplification of traits across a population, is still possible whether or not cultural information is ‘particulate’ in nature.16

In humanitarian innovation, the objects of innovation are commonly understood to be products, services, and processes, which are (ideally) adopted more widely.17 Within CET, the object of adoption (or inheritance) is simply “information that is acquired from other individuals via social transmission mechanisms such as imitation, teaching, or language.”18 In relation to innovation, such socially transmissible information might include but is not limited to pitch decks, theories of change, instruction manuals, guides, tutorials, or trainings. It is mostly not the ‘things’ themselves that are adopted; it is knowledge of how to replicate them.

CET goes on to suggest four mechanisms which generate variation in cultural traits. The first is cultural mutation, whereby unintentional changes to a trait are introduced through copying error. The second is recombination, whereby traits are combined. The third is guided variation, whereby a trait is purposefully improved during the course of transmission. The fourth is individual learning, whereby a trait is developed entirely through asocial individual efforts.19 In the context of CET, humanitarian innovation can be understood as the proactive introduction of new cultural variants, primarily through recombination and guided variation.20

Cultural selection occurs through a combination of content biases (the intrinsic attractiveness of an idea), indirect demonstrator biases (the positive characteristics of the idea demonstrator), and frequency-dependent bias (the tendency to conform based on current prevalence of an idea).21 I remember a colleague once telling me that “evidence is currency” in the humanitarian system. While this might be somewhat true, viewing adoption and evidence uptake through the wider lens of culture is arguably a more realistic perspective to take.

Importantly, cultural selection incorporates and builds on existing understandings of innovation and scaling. Most notably, Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations has provided much supporting evidence for cultural selection.22 For example, Rogers identifies relative advantage, compatibility, simplicity, testability, and observability as five characteristics of successful innovations. Within the context of CET, these characteristics have been reinterpreted as content biases that contribute to cultural selection.23 Rogers also wrote extensively about the importance of working through opinion leaders to demonstrate innovations.24

A critical precondition for cultural selection is ‘differential fitness’, or competition between cultural traits.25 This competition is fostered in environments with a ‘fitness function’ resulting from competition due to limited resources and an overcapacity of designs, along with other constraints such as physical conditions, political goals, or social values.26 The existence of such constraints means that some designs are more likely to succeed within an environment than others. It is these selection environments that shape the direction of cultural evolution, or in our case, humanitarian innovation.

Within CET, the concepts of ‘cultural group selection’ and ‘multi-level selection’ provide a basis for understanding cooperation within and between groups (and organisations), and describing how selection processes unfold across different levels.27 Understanding these selection processes and corresponding selection environments is key to understanding how ideas spread throughout communities, organisations, and sectors. It is also key to understanding how innovation misfires, for example, when sources of prestige in organisations are disconnected from real-world impact.

There is existing work to draw from here as well. In Maximilian Bruder and Thomas Baar’s review of humanitarian innovation, they advocate for the adoption of a mission-based ecosystem which would act to define the sector-wide selection environment, drawing from the work of Mariana Mazzucato and others at the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP).28 UNDP’s concept of ‘strategic innovation’ is focused on shaping the selection environment at the organisational level.29 And this is further supported by new thinking on innovation portfolio management.30

Within the field of biological and cultural evolution a distinction is made between ‘microevolution’, which studies the pattern of variation, selection, and inheritance, and ‘macroevolution’ which studies change at the population level31 — as with the aforementioned example of folktales. So far this article has dealt primarily with the process of microevolution, but the application of macroevolutionary research tools also offers promise for improving our understanding of how change happens and evaluating the success of innovations on a longer-term basis.

From what I have seen, evaluative research on scaling mostly takes a qualitative case study approach, drawing lessons from specific examples of success of failure in the relative short-term. Drawing on lessons from CET, phylogenetic methods, as well as econometric or history-oriented techniques, might also be used to test functional hypotheses for how and why ideas spread across the sector.32 Again, this is not entirely new. Certainly, econometric and network-based research methods have been employed more broadly, but perhaps less to examine such patterns of change over time.33

In summary: My aim in this post has been to provide a brief overview of cultural evolution theory, highlighting its relevance to the humanitarian innovation agenda and the potential of CET to provide a high-level theory of humanitarian innovation that is arguably lacking34 — and one that isn’t primarily derived from the private sector. Instead, CET is truly multidisciplinary, drawing from fields including psychology, anthropology, sociology, and organisational studies, as well as its origins in biology.

My interest in cultural evolution stems from experience of the limitations of ‘design thinking’ methods in supporting innovation, and the cottage industry of research and report writing on the perennial challenge of scaling. The humanitarian sector’s ‘innovation turn’ was grounded in the idea of innovation as a proactive endeavour, centring ‘the innovator’ in the process. From this perspective, systemic challenges are primarily barriers to be overcome by the innovation team, rather than opportunities for managers and policymakers to shape the environment for success.

The population-level view of ‘evolutionary thinking’ offers a necessary counterpoint to the innovator-centred view of design thinking. Evolutionary thinking encourages us to look beyond the challenges of scaling individual projects to examine how the wider conditions of the environment do or do not support the amplification of good ideas. It also enables us to look beyond a quasi-marketplace of products and services to situate innovation within broader conversations of how practical knowledge is generated, disseminated, and used.

In the context of CET, the innovation agenda, in general, has mostly paid attention to increasing variation in the population of intervention designs, but without paying equivalent attention to how we understand differential fitness and the processes of selection across the humanitarian sector that are necessary for innovations to succeed and scale. CET provides a language and orientation that offers more fruitful ground for thinking through these challenges, without departing very significantly from the models and frameworks more commonly referenced.

With perhaps just a dash of hyperbole, it has been suggested that CET holds the potential to synthesise the social sciences, providing an integrative framework for all social scientific research.35 On a basic level, evolution is a useful metaphor for telling the story of innovation which sheds light on some under-explored aspects. But it might also help us progress by providing better structure for research and policy. As Elinor Ostrom warned: “Without a common framework to organize findings, isolated knowledge does not cumulate.”36

I set up Evolving Impact to explore CET as a research framework for public and non-profit innovation, and as a broad set of tools or ‘rules of thumb’ for innovation in practice. I would love to hear if you’re interested in this work, if you see opportunities to collaborate, or if you have any suggestions for routes forward. As such, comments are very welcome, or you can email me at: ian@evolvingimpact.org

What else?

💭 In September Joseph Rowntree Foundation launched the Collective Imagination Practices Toolkit, a wonderful resource for thinking creatively about the future, bringing together content across six themes from a wide range of thinkers, practitioners, and artists.

🌐 A great new journal article on innovation portfolio management for public non-profit research and development summarises lessons from the private sector on the benefits of portfolio management, success factors, and challenges, and discusses their relevance to international development organisations.

🛠️ Brink have launched a new white paper on Innovation Carve-Outs, drawing from their extensive work supporting the Frontier Technologies Hub among other initiatives to map out a “systematic and intentional approach, capable of driving change across larger systems through continuous learning, improving, and scaling.”

📊 On the From Poverty to Power blog, Caitlin Scott argues that ‘the project’ is distorting the way international development organisations think and act, blocking transformative change. No where is this more apparent than in innovation where failure to achieve transformation is arguably a failure of piecemeal project-based approaches that largely ignore the politics of scale.

A final note

I started off thinking this might be a weekly newsletter but it turns out that I can’t really do short-and-sweet and I don’t have enough time for regular long posts. From now on, I’m aiming for every 2-4 weeks.

If you know anyone else interested in digging beneath the jargon and buzzwords to explore the nature of innovation and what it means for development and humanitarian impact, please share it with them.

I write as way to reflect, learn, and make sense of things, so everything is typed by hand without any inputs from AI. I sometimes use AI tools for brainstorming, research, and relating ideas, but all sources are cross-checked, reviewed, and referenced.

Tehrani, J.J. (2013) ‘The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood’, PLoS ONE. Edited by R.A. Bentley, 8(11), p. e78871. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078871.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html.

Darwin, C. (1874) The Descent of Man. London: John Murray. Original Edition, 1871. Available at: https://darwin-online.org.uk/converted/published/1874_Descent_F944/1874_Descent_F944.html

Mesoudi, A. (2017) ‘Pursuing Darwin’s curious parallel: Prospects for a science of cultural evolution’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(30), pp. 7853–7860. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620741114.

Ibid.

Mesoudi, A. (2016) ‘Cultural evolution: A review of theory, findings and controversies’, Evolutionary Biology, 43(4), pp. 481–497. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-015-9320-0.

Brahm, F. and Poblete, J. (2022) ‘Cultural evolution theory and organizations’, Organization Theory, 3(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211069141.

Beinhocker, E.D. (2007) The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. London: Random House Business. Available at: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/367805/the-origin-of-wealth-by-beinhocker-eric/9780712676618.

Dennett, D.C. (1996) Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. London: Penguin Books. Available at: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/15596/darwins-dangerous-idea-by-daniel-cdennett/9780140167344.

Ibid.

Mesoudi, A. (2016) ‘Cultural evolution: A review of theory, findings and controversies’, Evolutionary Biology, 43(4), pp. 481–497. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-015-9320-0.

Ibid.

Chvaja, R. (2020) ‘Why Did Memetics Fail? Comparative Case Study’, Perspectives on Science, 28(4), pp. 542–570. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/posc_a_00350.

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html.

Bruder, M. and Baar, T. (2024) ‘Innovation in humanitarian assistance—a systematic literature review’, Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 9(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-023-00144-3.

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html.

Brahm, F. and Poblete, J. (2022) ‘Cultural evolution theory and organizations’, Organization Theory, 3(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211069141.

While it’s certainly possible innovation might also come about via individual trial-and-error learning without a basis in socially-acquired information, I consider this unlikely in the context.

Mesoudi, A. (2017) ‘Pursuing Darwin’s curious parallel: Prospects for a science of cultural evolution’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(30), pp. 7853–7860. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620741114.

Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html

Ibid.

Rogers, E.M. (2003) Diffusion of Innovations. Fifth Edition. New York: Free Press. Available at: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Diffusion-of-Innovations-5th-Edition/Everett-M-Rogers/9780743258234.

Mesoudi, A. (2016) ‘Cultural evolution: A review of theory, findings and controversies’, Evolutionary Biology, 43(4), pp. 481–497. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-015-9320-0.

Beinhocker, E.D. (2007) The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. London: Random House Business. Available at: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/367805/the-origin-of-wealth-by-beinhocker-eric/9780712676618.

Brahm, F. and Poblete, J. (2022) ‘Cultural evolution theory and organizations’, Organization Theory, 3(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211069141.

Bruder, M. and Baar, T. (2024) ‘Innovation in humanitarian assistance—a systematic literature review’, Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 9(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-023-00144-3.

Bille Herman, M. and Xu, H. (2020) ‘UNDP’s Strategic Innovation Pivot’, UNDP Innovation, 10 December. Available at: https://medium.com/@undp.innovation/undps-strategic-innovation-pivot-4c2873aeee98.

Schut, M. et al. (no date) ‘Innovation portfolio management for the public non-profit research and development sector: What can we learn from the private sector?’, Innovation and Development, pp. 1–19. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2024.2400779.

Mesoudi, A. (2016) ‘Cultural evolution: A review of theory, findings and controversies’, Evolutionary Biology, 43(4), pp. 481–497. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-015-9320-0.

This has been proposed for explaining organisational phenomena in: Brahm, F. and Poblete, J. (2022) ‘Cultural evolution theory and organizations’, Organization Theory, 3(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211069141.

Ben Ramalingam provides examples of the use of network-based research methods in: Ramalingam, B. (2013) Aid on the Edge of Chaos: Rethinking International Cooperation in a Complex World. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/aid-on-the-edge-of-chaos-9780199578023.

Sandvik, K.B. (2017) ‘Now is the time to deliver: looking for humanitarian innovation’s theory of change’, Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 2(1), p. 8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-017-0023-2.

See: Brahm, F. and Poblete, J. (2022) ‘Cultural evolution theory and organizations’, Organization Theory, 3(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211069141; and Mesoudi, A. (2011) Cultural Evolution: How Darwinian Theory Can Explain Human Culture and Synthesize the Social Sciences. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo8787504.html.

Ostrom, E. (2009) ‘A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems’, Science, 325(5939), pp. 419–422. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133.

This was such an interesting article, thank you!